Years of Plenty

Memoirist Élisabeth de Gramont, born this day in 1875

April 23 is the birthday Élisabeth de Gramont was forced to share with William Shakespeare, and as far as I can tell, she never held it against him. Today is Shakespeare’s 450th birthday, Lily’s 139th. What’s an age gap of 311 years to an old soul descended from Henri IV? “Why,” I can almost hear her say, “we’re almost contemporaries!”

Lily de Gramont covers three centuries with grace and aplomb in her 1931 memoir, Years of Plenty, still fresh today. (New York: Jonathan Cape, 1931, 364 pp.) I just finished reading it, and I’m so glad I did.

I prefer admiring when possible, or else taking no notice.

–Élisabeth de Gramont, Years of Plenty

Years of Plenty is volume two of Lily’s four best-selling memoirs that came on the heels of her 1920 lifestyle classic, Almanach des bonnes choses de France. Chronicling Parisian life from around the turn of the century to the eve of World War I, it was published in French as Chestnuts in Blossom, perfect for April in Paris. So join me for a stroll through the Gilded Age down along the Seine. We’ll meet racehorse owners, writers, painters, poets, politicians, collectors, composers and “some famous foreigners”: pretty much everybody who was anybody in the capital of Europe.

Raised in wealth and privilege then left virtually penniless to raise two daughters after divorcing her husband in 1920, Lily earned her living with her pen. She was an astute and sensitive social observer with high energy. She aimed for a state of perpetual becoming. The key was fulfilling an insatiable appetite for people, places, things and sensual experiences. Her “eternal mate,” Natalie Barney, said she had a sixth sense for pleasure. As a young bride she wanders through Belle Époque Tunis like Cavafy in a corset, commenting on the “lovely lowered lashes” of the handsome youths in the Jewish quarter. She breaks off her sittings with Boldini when she realizes she “would have to pay one way or another.” Discretion must be maintained. She greedily eavesdrops on a reported scene of Sapphic seduction, with poet Renée Vivien carrying a woman up four flights of stairs, then halts the gossip when she learns Vivien is being “sumptuously kept” by another woman. The other woman is her cousin. She leaves that part out.

The “Ex-Duchesse de Clermont-Tonnerre” was as much a tastemaker as a social arbiter. The worst thing about poet-adventurer Gabriele d’Annunzio wasn’t his vanity, his profligacy, his womanizing or his facism; it was his poor taste in masquerading as a soldier. I found myself sharing the author’s impressions as if she were walking and talking beside me, not dead since 1954. She records styles that never go out of fashion and events that are either back in the news, or else they never left. “A few years ago,” for instance, Lily reports on art auctions, “Asia was being drained of its finest things by France.” Today the reverse is true, and our discussion would be totally au courant. On whether women need more confidence, the subject of a new best-selling book by Katty Kay and Claire Shipman, Lily de Gramont didn’t need three waves of feminism to teach her that confident women are “propped up in life by substantial realities.” And there are lots of other great homeland security tips in Years of Plenty: “Moral: if you have over three hundred guests, don’t leave your things lying about the house.” Or this helpful advice from her friend Edgar Degas: “one cannot have rugs and create things of beauty at the same time.”

Élisabeth is a beautiful writer because she worshipped beautiful writing from childhood. She spent much of the life of her mind on “imaginary snowy peaks reserved to poets; up there, each fresh snowfall awaits the imprint of new steps.” At 34 in 1909, she was the first to translate Keats into French. She used to carry the poems of Stéphane Mallarmé stuffed in her handbag; when she learned of his death, it was “a catastrophe.” The first living author she ever met was a memoirist; she was shy but undaunted by his Sixty Years of Recollections. The Norman poet Lucie Delarue-Mardrus was a childhood friend, and Lucie’s friend Marcel Proust soon became another one. Soon, Lily found that she was beginning to recognize the addresses of fictional characters in the streets of Paris. In a hilarious portrait of the Greek-born poet Anna de Noailles, Lily pokes fun at them both, reporting a complaint from a society hostess: “She comes in reciting Plutarch! I won’t have that sort of thing in my house!”

It’s the sensitive and soulful Lily de Gramont who touches me in this volume. I understand her lifelong love for Normandy (Hornfleur in particular) when she writes of Boudin as “the painter who succeeded in making the wind visible.” I understand her when she writes of Monet as a scientist and tells us that the water-lily ponds at Giverny were “a whole world of colonies and reflections that had been waiting to be painted until he came.” Rodin “practically invented the way to join bodies,” even though Lily’s friend Georges Clemenceau complained that Rodin made him look like a Japanese General. Entranced by the paintings of Van Gogh, “lemon juice must have been squeezed over that man’s palette to acidify his colours.”

This is the politically active daughter of a princess, a woman who was a Marxist from youth yet accepted her good fortune and couldn’t put her finger on what was wrong with Europe during the summer of 1914. She kept being “struck by the thought: It cannot last. Something’s about to happen.” Filled with foreboding, she left Paris for Marly. “I had a key to the forest, a huge, ponderous, rusty key which opened one of the massive Louis XIV portals leading to wide lawns and groves of lofty old trees. . . . All the structures of Marly put together, for which the King was so severely censured, cost exactly, in our money, the price of a day of war.”

In this memoir filled with grandees, geniuses and modern masters, the author sees them like the moon, either waxing or waning, rarely new or full.

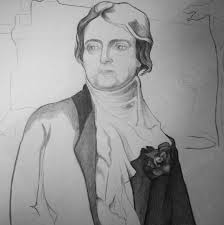

Thoroughly modern: Sketch for portrait by Romaine Brooks, whose rooftop dancing Élisabeth critiques in Years of Plenty

And she’s funny. She describes the Eiffel tower as a soil deposit, leaving it up to us to decide its chemical makeup. She admits that she coveted a few Van Gogh paintings, but his dealer “Hessel did not want to sell them to me, probably because it would have been hard for me to pay for them.” Isadora Duncan comes over for dinner with her new husband, Serge Essenin, who speaks no French. Drinking hard, he recites a long poem in Russian “which is, it seems, magnificent.” The only two words Lily can understand are lupanar (bordello) and syphilis. On vice: “Everybody has at least one—the English call them hobbies.” A male friend “rises so early that it must be to go to bed elsewhere,” which was also the habit of the woman she loved, Natalie Barney.

All her long life that spanned two world wars (she died at 79), Élisabeth de Gramont admired books that “explained woman’s mystery at a time when she still had some.”

She still has some.

Many happy returns of April 23, Madame. Your laughter is my string of pearls.

“Racecourses”

I live in a horsey country village flocked on the outskirts by some of the world’s loveliest training tracks—both flat and cross-country—still in private ownership. For ten springtimes I had the luxury of waking before dawn (if I could be bothered—anyone who knows me knows I am hardly a “morning person,” even on a mountainside) and taking a thermos down the road a quarter of a mile to stand at the fence and watch gallops on one of them. Nothing like it. The pounding of hooves at arm’s length wakes you more suddenly than any steaming cup of coffee. From that vantage point, you’ve never seen a tenderer sunrise. I’m not ashamed to say I’ve wept there on the rail on a few. One of the many reasons I’d never live anywhere else.

Middleburg, Virginia is a racing town electrified every April, and so I particularly enjoyed Lily’s chapter on “Racecourses.” Her father the Duc de Gramont kept racehorses at Glisolles in Normandy, and so she knew them well enough, although she admitted once to Baron Foy that she got bored trying to remember pedigrees, new rules and the latest in council politics. Writing in 1929, Lily counted more than ten newspapers devoted to horse racing, “as well as a page in every big daily…. Monday at Saint-Cloud, Tuesday at Enghien, Wednesday at Tremblay, Thursday at Auteuil, Friday at Maisons-Laffitte, Saturday at Vincennes and Sunday at Longchamp.”

Ah, those were the days, when Proust’s and Lily’s friend Robert de Montesquiou rued that he hadn’t been fitted by his Creator to be a stud horse. “When the intellectual looks on while a stud enjoys a triumph,” wrote Lily, “he perhaps envies such immediate and visible glory.”

Perhaps??? Indeed he does, Madame! Most everyone in Middleburg would agree. Here’s to those “colorful gleams in the fog” that awaken all the mornings of the world.

Perhaps??? Indeed he does, Madame! Most everyone in Middleburg would agree. Here’s to those “colorful gleams in the fog” that awaken all the mornings of the world.

Suzanne what a lovely love letter to an elegant birthday girl. No one does it better. Thank you for the post Romaine and Natalie would have been in total agreement with your take on Lily.

Ah, my darling, this is a pleasure…both of these posts are lovely and so evocative. Thank you.

[…] Pippa Gerber-Stroh, budding photographer, furnished the photos for Lily de Gramont’s birthday toast.Thanks, Sprite. […]

lgziwviuafzswcfkpxbnxkvazcafgmpgrzkhkfjwrxqatsmwyvhjkwxzcn

It is actually a nice and helpful piece of information. I

am satisfied that you just shared this useful info with us.

Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.