31 October 2014

life as a greek revival

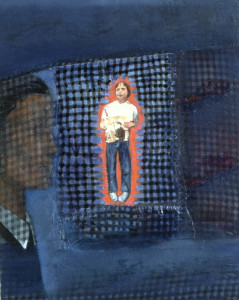

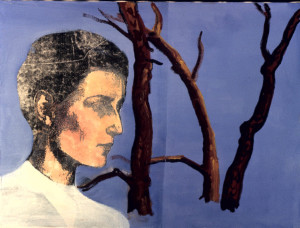

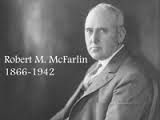

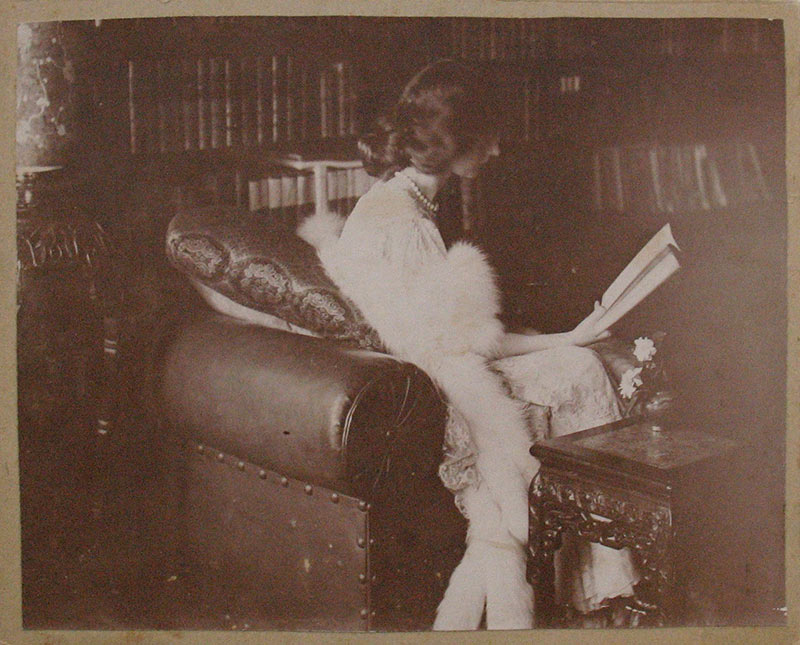

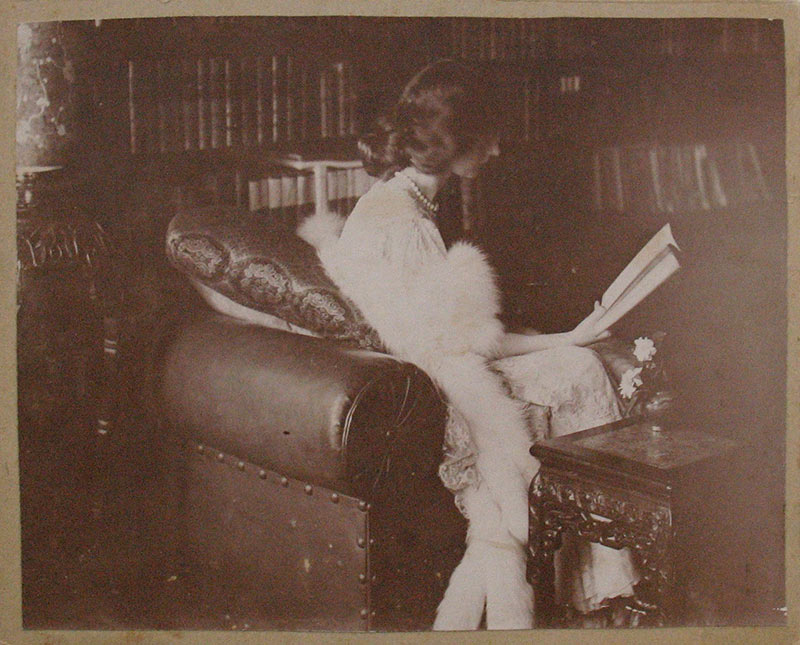

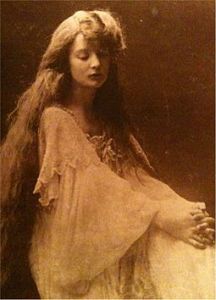

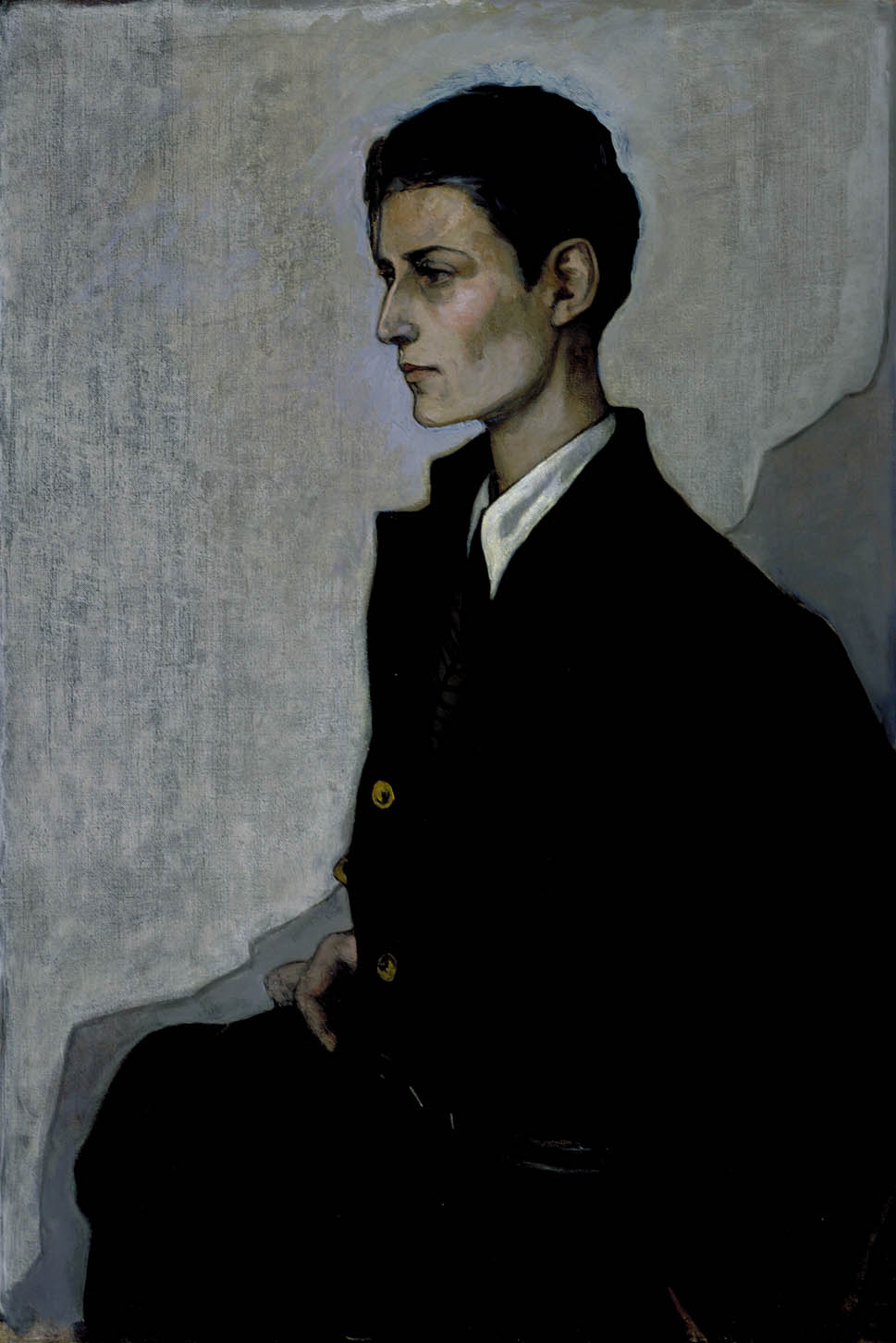

Eva Palmer (1874-1952) before her days “on the lunatic fringe”

“she was the only ancient greek i ever knew”

“she was the only ancient greek i ever knew”

a conversation with artemis leontis

Suzanne Stroh: Artemis, thanks for stopping by today on Natalie Barney’s 138th birthday. Here, have some cake. Lemonade?

Artemis Leontis: Thank you! Virtual cakes have essential vitamins to keep memories alive!

To augur many happy returns, I thought we could celebrate the life of somebody who made a profound impact on Natalie’s life, Eva Palmer-Sikelianos.You’ve been working on Eva’s biography. An incredible woman. Tell us about her.

Born into moneyed society in late-nineteenth-century New York, Eva was a non-traditional student, as most young women of her era were, with little formal training. Self taught, she passed the tough college entrance exams of Bryn Mawr College when she was 22 and studied Latin, Greek, and English there from 1896 to 1898. She left Bryn Mawr to accompany her brother in Rome (actually she was kicked out for a year); but she kept her dormitory room in Radnor Hall. When she returned to the U.S. in the summer of 1900, she offered it to Natalie and Renée Vivien to introduce them to the formal study of Greek and especially Sappho’s poetry.

She became a crucial link, you say. Connecting what?

Connecting the search for new identities and artistic forms with women’s classical learning in the early twentieth century. Her prodigious engagement with diverse leading artists had an influence that should be acknowledged in our reading of cultural history. She was, for instance, a founding member with Barney and Vivien of the Parisian cult of Sappho’s person known as Sapho 1900. She was instrumental in developments in modern dance from Isadora Duncan to Ted Shawn. She was a player in the Greek vernacular re-workings of ancient sources as exemplified by the poetry of Angelos Sikelianos, her husband; and part of the search for alternative tonalities for the revival of ancient drama, in dialogue with composers from Richard Strauss to Dimitri Mitropoulos. She was even connected to Gandhi’s advocacy of khadi in India’s decolonization movement.

Connecting the search for new identities and artistic forms with women’s classical learning in the early twentieth century. Her prodigious engagement with diverse leading artists had an influence that should be acknowledged in our reading of cultural history. She was, for instance, a founding member with Barney and Vivien of the Parisian cult of Sappho’s person known as Sapho 1900. She was instrumental in developments in modern dance from Isadora Duncan to Ted Shawn. She was a player in the Greek vernacular re-workings of ancient sources as exemplified by the poetry of Angelos Sikelianos, her husband; and part of the search for alternative tonalities for the revival of ancient drama, in dialogue with composers from Richard Strauss to Dimitri Mitropoulos. She was even connected to Gandhi’s advocacy of khadi in India’s decolonization movement.

Palmer mixed her women’s college Greek with American modernist and Greek national embodiments. And she gave flesh to Greek ruins to uncanny effect. According to one observer, “She had a strange power of entering the minds of the ancients and bringing them back to life again.”

But she was airbrushed. Brushed out of history.

Airbrushed from depictions of her era’s cultural attainments, Eva Palmer finds her place in this biography as a prominent figure in the portrait it paints of the group of modern artists and activists who sought to “make it new” by “making it old,” finding energy in the still remains of the distant past.

When you write that she was the most important foreign visitor to Greece since Byron, it seeds my imagination. I see reedy poets with slender flanks and flowing locks standing on blocky ruins. (In fact, I think I’ve seen a stunning nude photo of Natalie Barney taken by one of them there!) In that vision, Byron and Palmer do look a lot alike. But what impact did both artists really have on Greece? How did that compare to the fame of, say, Cavafy?

Cavafy’s poetry made him famous, especially after his death, and drew attention to him more than to Greece or even to Modern Greek poetry.

Byron’s two trips to Greece are another story altogether. His writing about Greece and especially his death at Messolonghi helped gain foreign sympathy for the Greek Revolution, which won its battle for independence from the Ottoman Empire largely through foreign support. Since his death, Byron has also served as a model for artists and individuals of romantic sensibilities (from Patrick Leigh Fermor to the hippies of Matala cave) who take up residency in Greece.

Byron’s two trips to Greece are another story altogether. His writing about Greece and especially his death at Messolonghi helped gain foreign sympathy for the Greek Revolution, which won its battle for independence from the Ottoman Empire largely through foreign support. Since his death, Byron has also served as a model for artists and individuals of romantic sensibilities (from Patrick Leigh Fermor to the hippies of Matala cave) who take up residency in Greece.

Palmer’s impact lies in the prototype she created for the development of Greece as a tourist destination. The Delphic Festivals, a large party she threw for elite guests at a beautifully located archaeological site with Greek drama, athletic games, exhibits, food, music, and dance to entertain them, had long-lasting effects. By her own largesse, she brought a large crowd of urban Greeks and foreign visitors to Delphi on a large cruise ship that anchored in Itea.

That was in 1927?

(Nods.) The crowd walked through the ruins along carefully landscaped paths she and Angelos had laid out. People viewed an exhibit of Greek handiwork from all the regions of Greece at Delphi and bought pieces as souvenirs. They tapped their feet to traditional music. They watched a performance of Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound and Suppliants in the ancient, open-air theatre, which used the living idioms of the Modern Greek language, music, and dance. Palmer’s work at Delphi bringing together all these elements became a template for the Greece’s post-War reconstruction under the Marshall Plan and helped shape Greece as a tourist destination.

Comparing her to Byron both artistically and philosophically, was Eva a romantic, a classicist, or something else?

Eva was an upper class American freethinker born into the Victorian era. She was deeply influenced by movements of her own time, from Delsartean principles to Arts and Crafts. She may be compared to Isadora Duncan for her backward glance to archaic art, and to modernists Ezra Pound and H.D. in their use of ancient prototypes.

With what mindset did she seek her spiritual home in Greece? An explorer’s? A pilgrim’s? A linguist’s? An artist’s? Something else?

I like to think of her as a kind of archaeologist.

When she first traveled to Greece in July 1906, it was for personal reasons: to escape from the perpetually triangular relationships of women in her circle with Natalie Barney. She wanted a more exclusive, tender relationship with Barney, but recognized that this was not forthcoming. So she came to Greece, a faraway land, so she might piece together her broken heart.

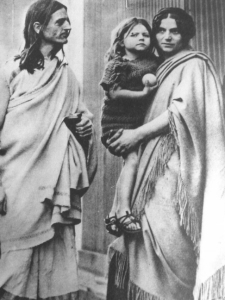

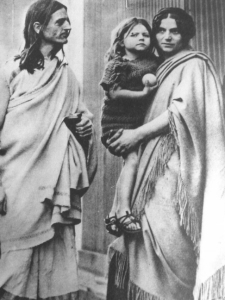

Isadora Duncan’s brother Raymond Duncan and his wife Penelope. Eva married Penelope’s brother, Angelos Sikelianos.

During her personal recovery she began to notice things beyond herself. Penelope Sikelianos Duncan–

Married to Raymond Duncan, Isadora Duncan’s brother.

Yes.

In September, James Conway wrote an interesting piece about Isadora and Raymond in Greece. But back to Eva. So her friend Penelope Duncan…

Penelope Sikelianos Duncan, Penelope’s brother Angelos, and their family and friends became her guides to the surrounding world. She was curious about Greece as an ancient place that was still alive. She soon spoke of Greece as a country, people, and language she loved. Digging deep into ancient ways of living, replicating ancient labor, relating the ancient Greeks to Greece’s present inhabitants, learning the language and processes of self care from people of the present, using all these things to animate the still remains of the past, helping Angelos and others around him fulfill their dream for contemporary Greece: these are the motives propelling Eva Palmer’s adult life from the time she began to find her footing in Greece.

What was her lifelong vision for the Greece of today—contemporary Greece, both in her own time and for our own?

She believed that pockets of Greek society retained a mode of living resistant to the automatization of the industrial era. She wanted—for herself and all Greece—to recover and preserve those processes of creation that were part of a traditional, un-mechanized way of life: modes of music making; techniques of spinning; skills in weaving and handiwork; ways of face-to-face socializing, poetry making. She saw in these things a potential model for sustainable modern living.

Would she say it has been realized?

She was never sanguine about the outcome of her efforts. She saw elements of her work appropriated selectively and put to uses she did not support.

Eva was a deep thinker as well as a practicing artist. What was her artistic journey? What conclusions had she come to, at the end of her life, about art, the creation of art and the appreciation of it?

I return to the theme of archaeology, the excavation of the material remains of ancient life. All her adult life she found inspiration in the gaps in the sources of knowledge about Greek antiquity, particularly lost textiles, sounds, and music. She used her hands, voice, and body to fill in the gaps. The body of work we should identify with her is her body and the traces of her actions and movements she left behind.

That’s profound. “Noticed but unrecorded” is I think the phrase Joan Schenkar used to describe the elusive life of Dolly Wilde. Is that the problem? Begging what approach?

I asked, how does Eva’s embodied replication of ancient life relate to archaeology, the disciplined study of human life in the past through its material remains? Eva Palmer did not consider her work archaeological in any formal sense. In 1900, she abandoned her studies in Greek and Latin at Bryn Mawr College to perform on the stage. When archaeologists congratulated her for her “archaeologically correct” production of Prometheus Bound at Delphi, she disclaimed accuracy in order to maintain artistic ends.

Politely. But firmly. Eva was insistent, speaking truth to power, and I was impressed. You read her comments aloud in your Athenian lecture. I looked at it here on Vimeo.

Yet Palmer pursued what she called an “anadromic method,” following the approach used to decipher the Rosetta Stone, to “remount the current” of history: to replicate ancient modes of weaving, composing, and dancing by comparing ancient sources with living practices. Her work is an example of “alternative archaeology,” that is, archaeological practices happening outside the formal discipline of archaeology. Alternative archaeology is useful to us here to consider what might be illuminated by an alternative, unscientific approach toward excavating ruins. Palmer’s creations bring into view the paths of non-experts in infusing ancient ruins with life and the vitality of such practices in this period.

At the end of her life, when she was composing music no one would ever hear and defending political positions that placed her on the Cold War blacklist of uncooperative artists, Eva described herself as working on a “lunatic fringe.” She may have felt she was drawing life from people who had moved and breathed long ago; but she felt increasingly alone among her living peers.

Which discipline was dearest to Eva in her heart? What work could she get lost in, and what came harder?

She sought to recover many different ancient processes: how Greeks wove and wore their clothes, recited poetry, improvised songs, staged plays, created art. She got lost in different media at different times. At the turn of the twentieth century, she dedicated herself to acting, costume design, and directing. From 1906 through 1915 she was absorbed by threadwork:, spinning and dying her own threads and weaving cloth.

Then for the next seven years she became a star student of neo-Byzantine-style Eastern Orthodox Church music, a very difficult non-Western musical system giving shape to thousands of hymns in ancient Greek. She made plans to open an international school for the preservation and instruction of non-Western music.

But that plan fell away, and from the mid 1920s through the late 1930s, she devoted herself again to the artistic direction, staging, costuming, and production of Greek drama. In the 1940s she composed hundreds of pieces of music for poetry and drama and translated Angelos Sikelianos’s poetry.

What came to her the hardest was any form of compromise that might help bridge her ideas with contemporary work that was appealing to American and even Greek audiences.

A scholar, a teacher, a traveler… an artist, a visionary, a wife and mother, a lover of women… so accomplished… Which of her accomplishments do you consider the greatest?

She saw the latent grandeur of the Greeks everywhere, and throughout her life she kept finding new ways to revive them: as the lover of women using Sappho’s words to express her feelings; the wife of a famous Greek poet who went “native” by adopting Greek tunics and advocating weaving to encourage Greece’s economic independence; the first woman to direct a major international festival of Greek drama and games in ancient Delphi; or the sibylline old woman who, upon returning to Greece in 1952 and suffering a stroke, was buried as a cult hero in Delphi.

Although she is best known for her direction of the Delphic Festivals, on which she spent all her money, this was by no means her culminating achievement. Instead what was extraordinary to me about her, and the story I wish to tell, is how she lived her entire adult life as a Greek revival. In the words of one young woman who performed in the chorus of Prometheus Bound under her direction, “She was the only ancient Greek I ever knew.”

Although she is best known for her direction of the Delphic Festivals, on which she spent all her money, this was by no means her culminating achievement. Instead what was extraordinary to me about her, and the story I wish to tell, is how she lived her entire adult life as a Greek revival. In the words of one young woman who performed in the chorus of Prometheus Bound under her direction, “She was the only ancient Greek I ever knew.”

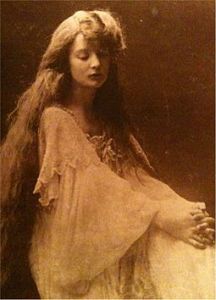

And she was very beautiful.

And she was very queer. I mean that in a very specific sense of the word. What do we make of the fact that she abandoned Western dress to wear hand-woven Greek tunics from 1907 to the end of her life? Queerness characterizes not just her sexuality but her peculiar untimeliness: “[N]o one who ever saw her felt that she belonged entirely in this world,” wrote Robert Payne, a British biographer, in his book The Splendour of Greece. To elaborate on her “out of time” existence, Payne quoted the words of one Greek woman who performed in Palmer’s production of Prometheus Bound.

“She had a strange power of entering the minds of the ancients and bringing them to life again. She knew everything about them – how they walked and talked in the marketplace, how they latched their shoes, how they arranged the folds of their gowns when they arose from the table, and what songs they sang, and how they danced, and how they went to bed. I don’t know how she knew these things, but she did.”

Robert Payne, The Splendour of Greece, p. 102.

Was she aware of her own beauty? What was the utility of beauty, according to Eva Palmer?

She was an introvert, perpetually in retreat from the attention of others, and at the same time an actor for whom the world was a stage. Her gray eyes and thick long auburn hair and endless posing inevitably brought attention to her. So her beauty in conjunction with her reticence helped her move in and out of the limelight. She could make herself quite noticeable, which really she did when she rejected the conventions of Western dress; and she was generally quite unforgettable. The world knew her as Eva Palmer, or Madame Sikelianou, wife of Angelos Sikelianos, and everywhere doors opened wherever she wished to enter.

“The mother of my desires”

In her memoirs, Natalie called Eva the mother of her desires. What did she mean?

The memoirs represent Natalie’s life as she wanted it to be remembered. Natalie’s words seem to mean that Eva was her first lover, who introduced her to same-sex female lovemaking in their shared adolescence. As far as I have been able to trace things, their relationship goes back to 1894, when Eva was 20 and Natalie two years younger. They may have known each other earlier, but I have not been able to trace it. I cannot confirm that Eva was the “mother of her desires” in the sense that it is normally taken. What matters is that Natalie in the company of Eva developed the repertoire of the cosmopolitan, artistic, Sappho-inspired, that is to say, lesbian lover. Together they helped to create roles and sensibilities and modes of inquiry to complement the lines of desire of the twentieth century lesbian.

But their relationship was very volatile.

Triangular love relationships were keys in their reading of Sappho’s fragments, and they replicated that rather unstable figure in their personal relations. Natalie in particular knew how to draw Eva toward her by putting another person between them. Volatility fanned the flames of desire—for as long as the desire was nourished; it was integral to the model. It also contained the seeds of their relationship’s destruction.

Name one or two things that Eva loved best about Natalie Barney. One or two things that drove her crazy.

Natalie’s wit. Her eyes. Her independence. She hated the insignificant lovers Natalie placed between them and her incessant need to please the people who mattered to her the least.

What qualities of Natalie’s probably contributed to their estrangement for so long? Any of Eva’s?

Eva writes that Natalie’s insulting treatment of Angelos Sikelianos drove her to marry him, and she shows that she was perpetually troubled, oddly, by Natalie’s conventionality and her disregard for Eva’s less conventional interests. I am sure Eva’s dependence on receiving Natalie’s approval was not an attractive feature. And Natalie never understood Eva’s loving embrace of Greek society, her “going native.” And she was completely insulted when Eva threw all their correspondence at her feet.

Natalie also threw her own birthday parties, inviting her inner circle that seemed to grow wider by the year. She formed a club of people born on the same day, like Marie Laurencin, and so Halloween chez l’Amazone was pretty festive. But Eva was an introvert. If Eva could whisk Natalie away on her birthday, where would they go and what would they do? Which one of Natalie’s 96 living birthdays would Eva dream of doing over?

Photo: unknown. Collection of Eleni Sikelianos.

Perhaps the one in the fall of 1905 when Natalie was 29 and Eva 31. As it happened, Natalie was in Paris while Eva was in New York arranging to perform Melisande to Sarah Bernhardt’s Pelleas in Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande. If that performance had gone according to Eva’s plan, if Sarah had been more interested in it and hadn’t tried to sabotage it by making Eva pay for the production, Eva would have invited Natalie to come to New York from Paris for the performance. She would have played her dreamiest Mélisande to win Sarah’s Pelléasian love. Natalie would have found Eva’s performance of the love scene of the fourth act scintillating. The bonds between them would have been recovered momentarily by Natalie’s jealousy of Sarah Bernhardt’s staged affection, Eva would have been hopeful of a new beginning between them, and both Natalie and Eva would have been all the more heartbroken when Eva left for Greece with Penelope Duncan.

(Speechless. Thinking: With Penelope Duncan???????)

I’m writing a screenplay about Natalie living with Romaine Brooks in Italy during World War II. I learned from you that Natalie and Eva met and reconciled shortly before Europe exploded in armed conflict. Tell me about that.

That was in May of 1939. Eva was in Connecticut recovering from double pneumonia, staying with her friend and possibly lover of the time, Mary Hambidge. She had just met Ted Shawn, the dancer and choreographer, and begun a test collaboration with his men dancers to see if they might stage Aeschylus’s Persians together. Either in Mary’s house or in the house of patron of the arts Katherine S. Drier, Natalie visited Eva.

The reunion was filled with good feeling and affection. Eva and Natalie had not seen each other since 1924. At that time Eva was a wealthy expatriate living a high life in Greece, visiting Paris on route to Germany, where she would test a special organ she had commissioned for her school of non-Western music. Now she was impoverished and unwell. She had no home of her own. Years of chain smoking and constant worrying over unpaid bills had worn her down. Life was fragile. Even so, opportunities still presented themselves. Here was Eva, on the point of a breakthrough with a performing artist who interested her and had doors opening for him. What was her point of readiness? What was Natalie’s point of readiness in a dangerous world that seemed to be falling apart?

Eva’s words to Natalie in a follow-up letter anticipate the fleeting opportunities and invisible landmines that had become a piece of her: “Because this everlasting striving to be what I should be, in order to properly accomplish the thing I feel worth while, these endless commands to myself, ‘Now do this, and now do that, and why don’t you do the other?’; has worked me into a sort of tension which three times has nearly broken me with serious illnesses.” Eva quotes from her favorite lines of special providence from Hamlet Act 5 Scene 2, 232 to 234.):

“If it be now, ’tis not to come,” for it becomes a sort of doctrine with me that whatever thing I most wished for would come to me if I myself were only ready for it. And this idea of Readiness can lead one far afield, for in any objective which is worth following at all, are there not endless byways which one should also be familiar with in order to reach this secret standard of Readiness.”

Most prescient of all, her letter to Natalie anticipates the danger to which Natalie was now returning in France. I almost sense that Eva is asking Natalie if she is ready for the difficulties she will be facing in the war.

Haunting, considering the timeline I’ve been able to piece together with the help of Langer and Rapazzini. She was in danger. Lily de Gramont knew it and had written to Natalie from Hornfleur, begging her to bring money and bring Romaine Brooks and get out of France. Natalie wrote back three heartbreaking words: NOT WITHOUT YOU. She knew Lily would never abandon her country in wartime. They’d spent the first war together, with Lily assisting amputations at the train station every day, and Natalie believed it was in her power to make sure they would not be parted during the second. But she was wrong. They were separated for six years. How did Eva spend the war years?

She wove costumes and wrote music for Ted Shawn’s dance group. Then, when the group was dismantled and their collaboration fell apart, she stayed with Mary Hambidge in the artist residency Mary was creating in the mountains of northeast Georgia. When their relationship came undone, she moved to New York to be near her friend Elsa Barker and brother Courtlandt. She composed music, corresponded with friends, translated and published Angelos Sikelianos’s poetry in English, and sent hundreds of political letters to politicians and newspapers, protesting the international sidelining of the leftist resistance movement EAM in the transition from the German occupation to civilian rule in Greece and the return of the Danish monarchy.

Her political positions shifted further to the left, and, by the end of the war, she was identified by some as a persona non grata. She tried but was unable to publish her autobiography, Upward Panic.

Her political positions shifted further to the left, and, by the end of the war, she was identified by some as a persona non grata. She tried but was unable to publish her autobiography, Upward Panic.

Panic, in the sense of that rustic god with the thrusting energies, not panic the onrush of dread.

In both senses. Panic is the rush of dread brought on by Pan, the rustic god with thrusting energies. Panic can move people downward or upward.

It was finally published in 1993. Here’s an Amazon link to it, edited by Professor John Anton.

Natalie’s sister, Laura Dreyfus-Barney, spent the war in Washington, DC. The sisters were one quarter Jewish, which made them a target in Paris. But Natalie was in denial. Laura may have been more realistic since she had been married to a Jew, Hippolyte Dreyfus, and even though Hippo had died in 1928, Laura left France in 1939 just as she had done in 1914. But Laura’s sociable mother Alice had died back in 1931. The house must have felt very empty. I’ve often wondered if Laura was lonely during those years spent separated from her sister. Were Eva and Laura close?

I don’t know anything about their relationship. Laura strikes me as a person of enormous social and administrative skills. I have no evidence that Eva sought her out in any way from 1933 to 1952 while she was in the U.S.

What other personal and professional relationships were central in Eva’s life and development?

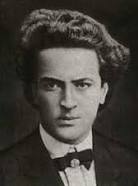

Angelos Sikelianos (1907-1934) Greek poet and playwright, married to Eva Palmer

Angelos Sikelianos was a significant influence. They were lovers only briefly but collaborators for a lifetime. She opened doors for him with her money, and he made her welcome in ethnically Greek circles. She did everything she could to promote (and perhaps give direction to) his work. The other major figures I have not yet mentioned are Konstantinos Psachos, the professor of Byzantine Music and head chanter who taught her Byzantine music and wrote the music for the choruses of the Delphic festivals; and Khorshed Naoroji, a Parsi woman from an eminent family who studied classical piano at the Sorbonne University and collaborated with Eva to form a school of non-Western music. The school never opened, because Eva turned her attention to directing the Delphic Festivals and Khorshed returned to India, took khadi voiws, and joined Gandhi’s movement.

Sounds like you’ve been on an Odyssey of your own as Eva’s biographer. Tell me what it’s been like to write this book. What has surprised you most?

The spread of her connections and the number and quality of extant traces of her life. The bifurcation of her biographical presence as Eva Palmer, Natalie Clifford Barney’s lover, and Eva Sikelianou, Angelos Sikelianos’s wife. For years no one followed readily accessible traces to connect the parts. I knew her as the Greek poet’s wife, and she was for me a mystery figure. I could make neither heads nor tails of Eva’s strange presence next to Sikelianos. I had no way to decide if she was subsidiary or important, interesting or indifferent. Once I found that she played a seminal role in organizing the cultural events for which she gave her husband credit and that her sources of inspiration lay in college women’s Greek and “Sapho 1900” in addition to Greek vernacular culture, I began to seek out archives relating to her life.

So far I have visited libraries and museums in New York, Massachussets, Washington D.C., Maryland, Wisconsin, Paris, Delphi, and Athens. Every chapter of her life feels like a fresh start. What has surprised me most is the size and breadth of her network and the depth of her relationships at many important turns in her life. I am also taken by her calm demeanor in the days before she died, when she returned to Greece and posed, sibyl-like, in the theatre at Delphi, as if announcing that the oracle of Delphi is no more. At key turning points she anticipated the turn her life will take.

Once again, haunting. Perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised. It’s All Hallows Eve.

Then it’s appropriate that Eva haunts us. Thank you for your questions! I am grateful for every opportunity to cross check sources and interact with another researcher and thinker.

It’s been my pleasure, too. Thanks so much, Artemis. Best of luck on your book, which I can’t wait to read.

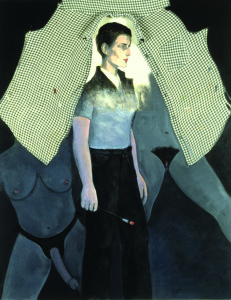

The oracle at Delphi is no more. Eva Palmer-SIkelianos (1874-1952)

Artemis Leontis is Professor in the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan and teaches Modern Greek and Comparative Literature.

Her books are Culture and Customs of Greece (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2009), an introduction to Greek culture for a broad educated readership, and Topographies of Hellenism: Mapping the Homeland (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995).

She is the editor of Greece: A Travelers Literary Companion (San Francisco: Whereabouts Press), an anthology of essays and short stories translated from Greek, and “What These Ithacas Mean….” Readings in Cavafy, a bilingual, illustrated presentation of selected works by Cavafy.

She is currently completing her longtime biography project, “A Life in Ruins: The Alternative Archaeologies of Eva Palmer Sikelianos.”

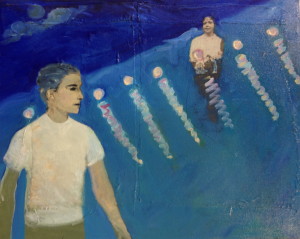

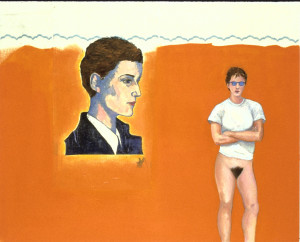

The Peter Paintings

The Peter Paintings