Waking Up French

Waking Up French

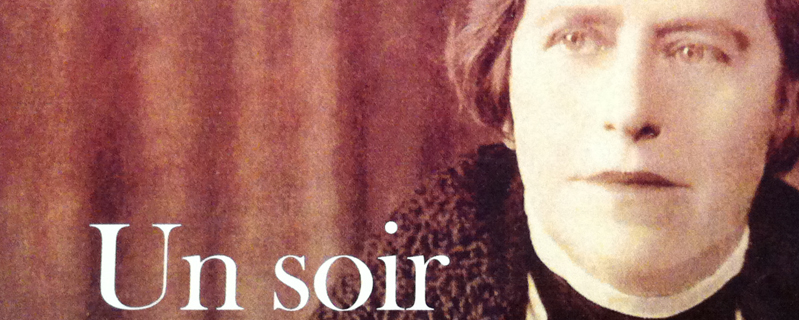

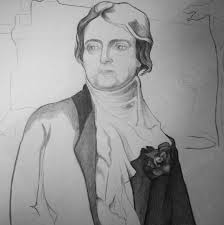

Ren ée Vivien (1877-1909)

and the French language Revival in Maine

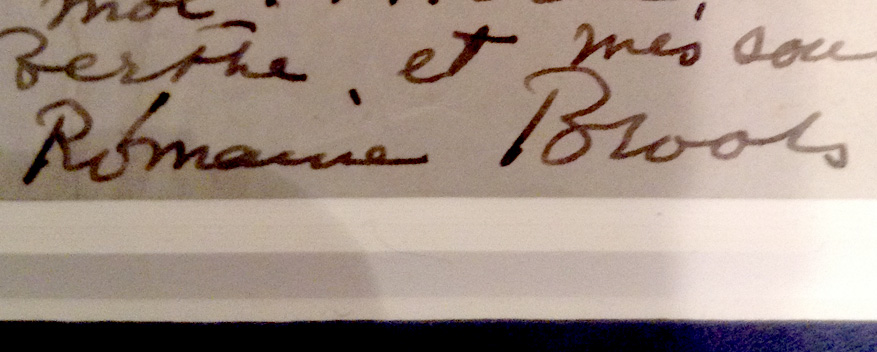

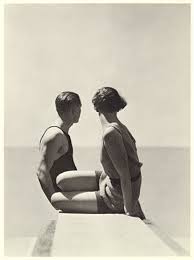

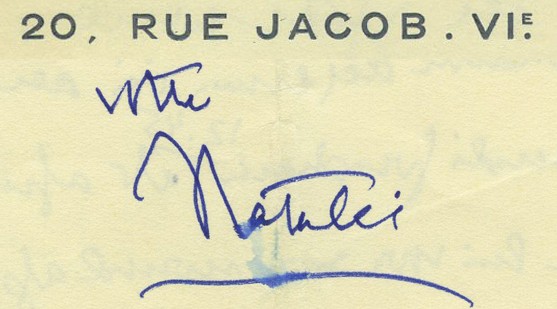

June 11 is the birthday of the French Symbolist poet Renée Vivien, who wasn’t really French at all. Nor was she called Renée–at least not by those who loved her, like Violet Shiletto, Eva Palmer, Natalie Barney, Romaine Brooks or Hélène de Rothschild. They called her Paule.

In Memoriam

If you love French language, French film, Cajun music and French culture, join me in making a small donation—anything you can afford—like the one I will make every year on June 11 to the Renée Vivien Poetry Fund, a memorial I set up last year at the University of Maine at Augusta.

Waking up French in the state of Maine has never been easy. Along with their Cajun cousins, Maine’s native French speakers have been scoffed at and discriminated against for decades, according to Chelsea Ray, the UMA French professor who helped to build a French after school program for kids that’s “a symbolic first step as a corrective for this discrimination.” (Annie Murphy of Public Radio International did a great story on it for “The World” back in March. View the PRI story here.)

Ben Levine’s documentary film REVEIL revisits this dark history and lights a creative spark.

Let’s make lasting change by providing funds to seed an arts festival scene in Augusta that will rejoin Cajun music and Acadian dialect in film, theatre and poetry for the young people who want to emerge from the shadows and embrace their French heritage full on, beyond conversation into arts and letters.

Renée Vivien: Petit Paule

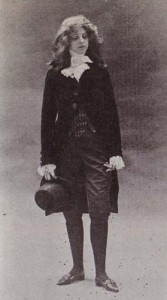

She was born Pauline Tarn in London 137 years ago today. Her mother was from Jackson, Michigan. Her father inherited a merchant fortune that Pauline’s mother was determined to control. I’ll pass over her privileged but troubled childhood to the day when she woke up French on her 21st birthday, a bit like Orlando waking up as a woman in Virginia Woolf’s charming novel.

From that moment on, after regaining control of her fortune held in trust, it was across the Channel and no looking back. Pauline escaped her mother’s clutches and moved to Paris to live, breathe and write poetry in French. She took the pen name Renée Vivien for “born again.” Steeped in Greek and in-depth study of French, her poetry was classical (Lucie Delarue-Mardrus and Colette called it old fashioned) and exquisite with decadent Symbolist themes, dragging the 19th century into the 20th and earning her a place in the Pantheon beside Baudelaire.

From that moment on, after regaining control of her fortune held in trust, it was across the Channel and no looking back. Pauline escaped her mother’s clutches and moved to Paris to live, breathe and write poetry in French. She took the pen name Renée Vivien for “born again.” Steeped in Greek and in-depth study of French, her poetry was classical (Lucie Delarue-Mardrus and Colette called it old fashioned) and exquisite with decadent Symbolist themes, dragging the 19th century into the 20th and earning her a place in the Pantheon beside Baudelaire.

Another way you can make a real difference in young people’s lives today is to make a small donation—which I am also doing—to UMA’s scholarship fund for the study of French. It’s directed by Chelsea Ray, the UMA French professor who translated Natalie Barney’s 1926 erotic novel.

Here’s a message from Chelsea Ray:

Thank you very much for offering to help with my work at UMA. I work primarily with the Franco-American community here; it is a vibrant community that withstood much discrimination.

I am the only faculty member who teaches French on campus; indeed, I am the second full-time tenured faculty member in any language in the history of UMA. I have created a very efficient program, running 200 and 300 level classes at the same time and bringing teaching assistants from the University of Western Brittany to UMA each year. We do not have dorms or any student housing whatsoever (UMA is the only public campus in the UMaine system not to have housing), so I am obliged to also locate host families for the French students, or locate “starter families” to help them get settled. As chair of the International Advocacy Committee, I have my work cut out for me, especially in a state like Maine where students often do not feel drawn to international issues and have no funds to travel.

The best way to help my work would be to donate online to the newly endowed Marcel Raymond Scholarship for the Study of French at UMA. It allows UMA students to travel to France for the first time, on an immersion exchange with the University of Western Brittany. These students often have little to no funds for travel; they can barely take off a weekend of working, let alone three weeks. This fund will provide two students with funding for travel, participation in our annual immersion weekend program, or other immersion opportunities.

I hope you will consider this option, and encourage others to do the same.

If you have additional questions, contact Staci Warren in the Office of University Advancement: (207) 621-3299.

I think that this scholarship fund can be seen certainly in the spirit of Renée Vivien herself, who was so inspired by the study of French.

I cannot thank you enough for your generosity and help in supporting French at UMA.

Best wishes, Chelsea

“In the Spirit of Renée Vivien Herself”

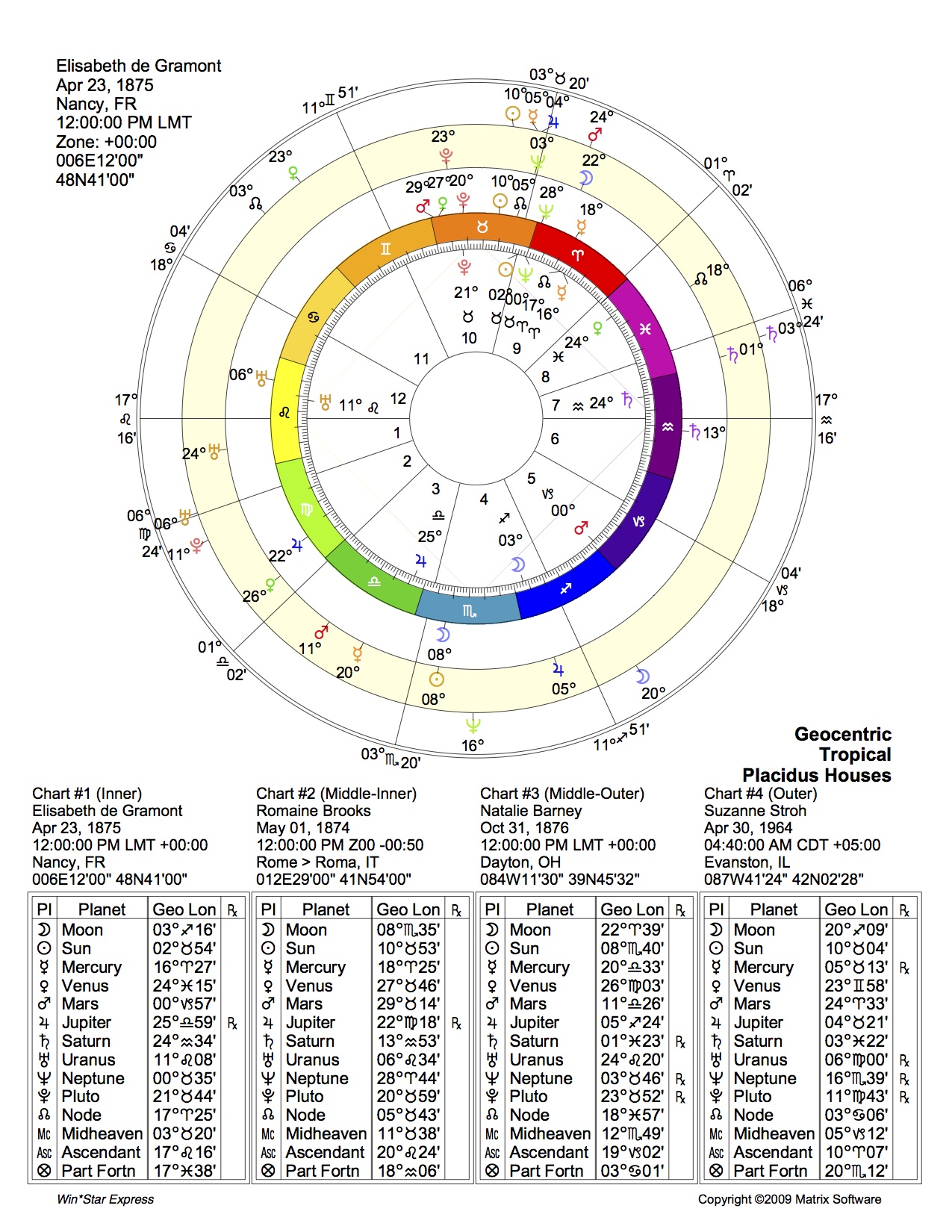

Starting rich and ending ruined shortly thereafter, the poet’s life was Bohemian by any standard. Think of her as a female Rimbaud who dressed like Hamlet, attracted rich and powerful lesbians then carried them up four flights of stairs, according to Lily de Gramont. She was very pretty and very addicted to chloral hydrate. So addicted, it seems, that her body failed to respond in lovemaking with Natalie Barney, the love of her life.

Natalie was highly sexed and sought her pleasures elsewhere. Pauline, as a pure Romantic, struggled with Natalie’s classical attitude to love and sex. In the end, she left Natalie for infidelity and wrote a very bad crepuscular novel about their split, A Woman Appeared to Me, which perhaps unwittingly centers around the next woman in her life, Romaine Brooks.

The breakup with Barney sent Pauline spinning out of control. Brooks bailed. Hélène de Rothschild, now Baroness van Zuylen van Nyevelt and still immensely rich in spite of having been disinherited for marrying outside the faith, tried to right Pauline’s ship with equal doses of travel, domesticity and self-publishing. It didn’t work. Hélène fell in love with another woman, took Pauline off her payroll and moved to Lisbon.

Late in 1908 we find Pauline ravaged by drugs, emaciated by anorexia, broke and suicidal, still tortured by her rejecting love of Natalie Barney, and dangerously addicted to sadomasochism, according to Colette in The Pure and the Impure. The sex addiction was an irony Natalie Barney never accepted. She told Colette that she didn’t agree with Colette’s take on Renée. The truth was too much for Natalie to bear, even though she suffered from a milder case of sex addiction herself.

Natalie arrived on Pauline’s doorstep with flowers one morning in 1909 to find her dead at 32. Hélène took the nosegay and blocked the door. Natalie walked a block and fainted on a park bench. Recovering her senses, she sought comfort in the arms of the second great love of her life, Lily de Gramont. There she confessed her guilt over Pauline’s death, caused (she believed) by the chronic infidelity that Natalie was powerless over. Lily was an atheist who decided, there and then, to grant Natalie absolution. It was obvious to Lily that Natalie’s guilt had the power to destroy her, and Lily refused to let that happen. They were together from that moment for life, until Lily’s death in 1954.

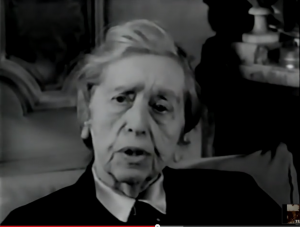

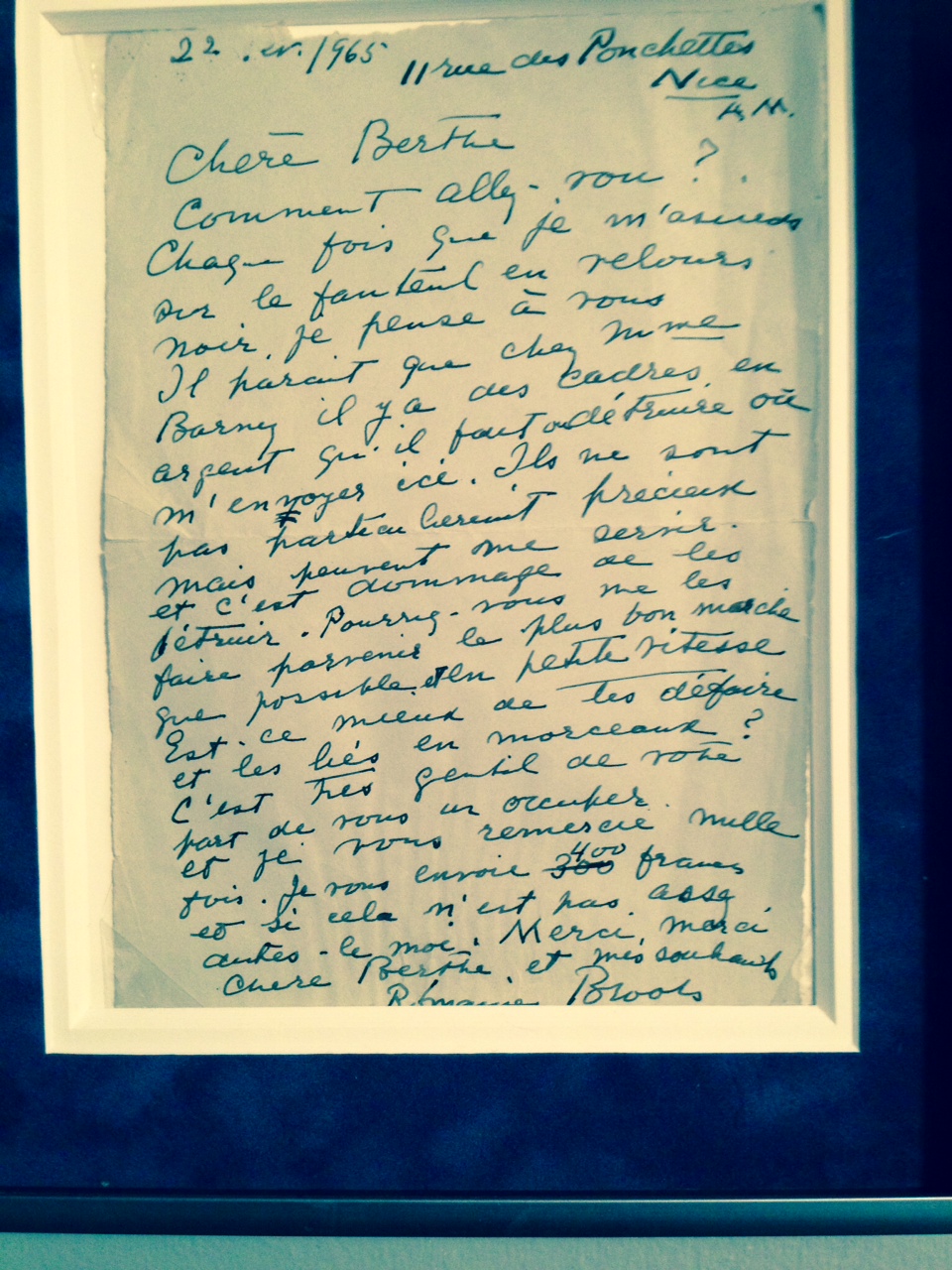

In the middle of that remarkable love story flowered another, equally beautiful, perennial love. Natalie and Romaine Brooks met in 1916. Their shared possession of the dead Pauline was a simple reality in their love story, which also lasted a lifetime from that moment, until Romaine closed the door in preparation for her own death in 1970 at 96. Natalie followed two years later, also aged 96.

In translating the biography of Élisabeth de Gramont (Hélène’s cousin), I see evidence that both women, Romaine Brooks and Lily de Gramont, spent considerable amounts of time protecting Natalie from herself and from the ghost of Renée Vivien, a great American poet who kept failing at life. Her major subject, like Poe’s, was death.

In translating the biography of Élisabeth de Gramont (Hélène’s cousin), I see evidence that both women, Romaine Brooks and Lily de Gramont, spent considerable amounts of time protecting Natalie from herself and from the ghost of Renée Vivien, a great American poet who kept failing at life. Her major subject, like Poe’s, was death.

Requiescat in pace. May you wake up in French.

The after school French program at Sherwood Heights Elementary School in Auburn, Maine, is where kids learn the local French their forbears have spoken for generations. You know, like in Evangeline, that gorgeous 1847 poem by Portland-born Henry Wadsworth Longfellow that I had to memorize in sixth grade:

This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks,

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of old, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.

Loud from its rocky caverns, the deep-voiced neighboring ocean

Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the forest.

–Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Evangeline

So haunting. Ren ée Vivien must have loved it. Brother and sister recite it together in Patience, Book 1 of my quintet of novels, TABOU. (You can buy TABOU for your eReader on the Books page of this website.) Now, I learn, Evangeline wasn’t just a saga. It was a protest poem against British treatment of French natives in Acadia, now Nova Scotia.

Le Grand Dérangement

Acadiens were French emigrés to Canada whose culture and language developed independently of the Québecois. Retaining elements of Vivien’s beloved 17th century French, Acadian French is a lost dialect everywhere else in Canada and in France.

As for the Acadiens themselves, their Arcadia in Acadia was short lived. After three generations, the region was conquered and Acadiens lived under British rule for another generation and a half until 1775, when they were expelled from Canada. Many drifted down into Maine and settled south of the Kennebec; others ended up as Cajuns in Louisiana.

Rockland-based filmmaker Ben Levine wanted to understand “what it meant to be French” for the descendants of these Acadiens. His documentary REVEIL explores “how they felt about losing French and what they could do to bring it back. The older generation is retired now. They were working class people with an oral culture that inherited its strengths and weaknesses from being isolated by the English.” But discrimination was everywhere. “Frog” was an ethnic slur. Levine uncovered evidence of Ku Klux Klan involvement in the 1920s to eradicate French culture from Maine. Cajun Acadiens suffered the same discrimination that has informed their music ever since.

“For the younger generation,” Levine says, “we see the waking up process, [realizing] that they are French and still can be French.” They have reclaimed the slur, calling themselves Farogs. The broader community is now mainstreaming more and gathering together, from the Upper St. John Valley (historically, home to the Acadiens) to the industrial mill towns of Southern and Central Maine: Biddeford, Lewiston, Augusta and Waterville (historically, home to Americans of French descent).

The film, subtitled WAKING UP FRENCH, has staying power. “Even now we’re still showing it to public audiences,” says Levine, witnessing the French cultural revival stretching from Louisiana up to Maine, cross-pollinating with the thriving Cajun music scene. “We’ve got bands singing in New England French. There’s singer Zachary Richard. There’s Greg Chabot, the playwright. Marie Cormier is producing French plays. Denis Ledoux is a Franco-American writer living in Lewiston.”

“There’s a whole younger generation of Franco-American writers now,” says Levine’s co-producer Julia Schulz. “It’s an exciting literary movement.” I can see a natural blend of well-attended poetry readings and music festivals on the horizon when Levine adds: “We’re seeing French majors who become high school French teachers. They do their PhDs in linguistics, then they do more research.”

All this means that the oral culture which has kept Acadian French dormant into the internet age is about to flower in arts and letters. Worldwide, 300 million people speak French in 29 countries where it is an official language. For the Farogs down east, the days of secrecy and shame are over.