Screenwriter’s Notebook

Garbo Slept Here

I was working in Los Angeles last week, which played havoc with my writing routine. To clear my mind and reset, it helps to lose track of time.

Back when Paris was a woman, Natalie Barney reported “getting more out of life than it perhaps contained.” And that’s just what I was doing the other day, motorcycling in Death Valley. Flying past the Furnace Creek Inn faster than a fleeting thought, I thought again. After watering my silver steed, filling the tank with hi-test at $5.56 a gallon, I made a u-turn and headed back to the folly up the road.

Long tall drink of water at The Inn at Furnace Creek

Furnace Creek is one of those desert hideaways of Hollywood’s Golden Age. It was quite the hot spot in 1927 when it opened with twelve rooms to cool the brow of the Borax King, Francis Smith, and his No. 1 Pitch Man, Ronald Reagan.

Two years later, in 1929, Natalie’s playwright mother Alice Pike Barney took her Washington, D.C. show on the road and ended up in Los Angeles. She staked the Theatre Mart on North Juanita and opened with her own plays.

Natalie and her mother were writing partners specializing in witty comedies. (Think Oscar Wilde meets Bertie Wooster). When Natalie found out that Alice had put on their plays without crediting her work, Natalie went magnesium hair on fire.

There was only one thing for it. Jump on a transatlantic steamship and hop a Barney car for California. Tedious, but then Natalie was an Epicurean who never tired of sampling the feminine fare on her travels. She knew how to savor the moment: one delectation after another. Stopping over for Christmas in New York with Romaine Brooks, Natalie left for the coast sometime in early 1930.

Thanks to Wild Heart by Natalie’s biographer Suzanne Rodriguez (read her interview here), we know that mother and daughter had one catfight of a writers’ quarrel. We know Natalie planned to lecture Alice about her lying, cheating, spendthrift ways. After all, there was a Wall Street Crash on! But when Natalie got to Los Angeles and took one look at her 70 year-old mother becoming the toast of Hollywood, she couldn’t bring herself to browbeat her high-spirited “Little One.” Did they trundle along to Death Valley to make up? Would I find Natalie’s name in the hotel register?

I dismounted and walked up the drive that snaked the date-palmed hillside. What I love about these old-time resorts is their understatement, their impeccable taste and their modest scale, compared to the leisure behemoths of today. If you’ve ever been to the Arizona Inn in Tucson, you know what I mean. Never mind that here in the Nevada Desert, I was entering the foyer of a totally unsustainable folly of mad architectural obsession, elevation 190 feet below sea level. On a perfect November day, everything about life on this desert planet was cool, calm, collected and scaled beautifully to suit the Garbo-like creature sitting out on the terrace, I furtively noticed…. instead of being scaled to life on that moon in AVATAR with those big blue people from Vegas.

I dismounted and walked up the drive that snaked the date-palmed hillside. What I love about these old-time resorts is their understatement, their impeccable taste and their modest scale, compared to the leisure behemoths of today. If you’ve ever been to the Arizona Inn in Tucson, you know what I mean. Never mind that here in the Nevada Desert, I was entering the foyer of a totally unsustainable folly of mad architectural obsession, elevation 190 feet below sea level. On a perfect November day, everything about life on this desert planet was cool, calm, collected and scaled beautifully to suit the Garbo-like creature sitting out on the terrace, I furtively noticed…. instead of being scaled to life on that moon in AVATAR with those big blue people from Vegas.

In consummate Barney style, I had arrived in time for Sunday brunch, which I thoroughly enjoyed out on the terrace in the company of two equally decorative Canadians—Garbo and her man-of-the-moment. Ah, that was a long, tall drink of water to remember.

Greta Garbo in 1933

As Garbo understood so well, talk comes easy in the desert. Maybe because it’s never forced. You can always have desert silence together, which is even better. So our main subjects drifted effortlessly to the Calgary Stampede and the fortune they made in lighting design, having invented the electronic control systems for all the Vegas shows. Relishing my last fresh produce before the one-pot camp cooking that awaited me at dusk, I was reminded of Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood. He wrote that the rich are different from you and me. In Canada, they are always nicer.

The idle hour we spent together wasn’t enough time for the inn’s general manager to check the hotel register. I had to suit up, pop the clutch and roll on with nothing more than a hunch that my path had crossed with Natalie’s. And Greta’s?

One Desert Queen to Another

Albert Johnson survived the train wreck that killed his father, inheriting an income of a million dollars a year.

Fifty miles up the road from Furnace Creek, you find the shadows lengthening in Grapevine Canyon. That’s at the back of beyond where another railroad scion of Natalie Barney’s generation, Ohio-born Albert Johnson (1972-1948), built his own Iberio-Tuscan folly on 1,500 acres at Death Valley Ranch.

Bessie Johnson’s variation on the rustic hunting lodge

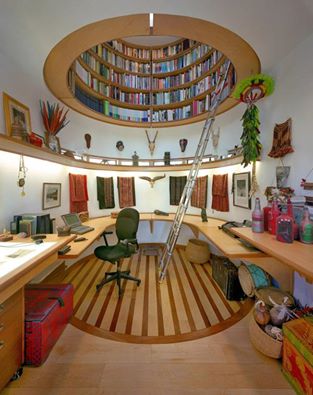

A house that would not be out of place in Pasadena does not necessarily belong in the Nevada desert. I cocked my head like a dog, trying to take in the extraordinary sight before me. Clock tower: check. Carillon: check. Giant Zorro sundial above fortified courtyard: check. Bunk house out of a John Ford western for staff, decorators and rough trade: check. There’s something wrong with the scale, I thought, feeling completely dislocated.

As I paid my ticket and walked over to the tiled fountain to meet the last National Park Service house tour of the day, it felt like I’d rolled back several Golden Ages with every mile under my pegs.

DO NOT BACK UP! SEVERE TIRE DAMAGE!

Just like a scene out of Lettice & Lovage, the tour was immediately punctuated by cactus quills in the courtyard, even though I had been archly advised not to try getting the entire sundial in the viewfinder. I spent the next hour picking hair-like slivers out of my backside and trying to pay attention to the crazy narrative.

Johnson was a Cornell-trained, frustrated mechanical engineer with a Don Quixote fetish and a hankering for solar-powered Wurlitzers. It seems Johnson and his equally eccentric heiress-wife Bessie (of the proto-Martha Stewart variety) had cloaked their enigma in a mystery.

The mystery was Death Valley Scotty, a charlatan so famous that he got 500 fan letters a day—roughly equivalent to Garbo’s take–according to author Richard Lingenfelter in Death Valley and the Amargosa. Scotty had lured Johnson and other east coast investors west with tales of gold in Grapevine canyon. It was never found, of course.

Don Quixote with Sancho Panza (Death Valley Scotty) and Martha Stewart, c. 1930.

But Johnson kept Scotty as collateral, and he served the bullshitting wildcatter up to houseguests well into the 1940s. It really was something out of the American subplot in a P.G. Wodehouse novel.

The Johnsons never had children, I noted, even though Bessie wrote luminous poetry about being naked in the moonlight. (“Give me desert moonlight/every time!” quoth the tour guide from Bessie’s privately published complete works.) Hmm….

Should I have been surprised to learn that Garbo slept here? Should I have asked to see if Natalie Barney ever signed the guest book?

Guess who’s coming to dinner?

Well, I’ll cut the tour mercifully short and cut to the chase. I had a heavenly ride back to Furnace Creek, full of sage scent, and pitched my tent in the dark under a silvery full moon. Firing up my isobutane burner, boiling water to rehydrate my freeze-dried supper, I thought I could hear echoes of the mighty Wurlitzer bellowing faintly in the distance, mingled with Scotty’s tall tales, Albert’s manly talk of water-cooled interiors and Bessie’s poetic intonations cutting Greta’s deep silences.

And then too soon, as it always happens, civilization got me in her grip again.

Did They or Didn’t They?

When Garbo slept here, who slept there?

With power back to my iPhone, I emailed my go-to Garbo expert Diana McLellan, author of The Girls, one of the most entertaining books ever written about lesbians, Hollywood and spycraft—that most excellent pairing. If you haven’t read The Girls, really you must.

When exactly did Garbo stay there, I wondered, and do we know anything about her visit? What did she think of that bizarre place in the smack-dab middle of hot-as-hell nowhere?

Garbo’s co-star in Queen Christina, Barbara Barondess, called Garbo a tightwad. “She used to come into my shop on Wilshire Boulevard and talk. I think she was the dullest woman I ever met.” Not a woman prone to introspection about her rich friends. (The Johnsons, reportedly, were Greta’s neighbors in Beverly Hills.)

Diana McLellan believes that Greta’s Death Valley idyll may have unfolded while she was filming QUEEN CHRISTINA in 1933—not 1930. Greta had a crush on her director, Rouben Mamoulian. She’d been planning to escape on a mini-break with Mercedes de Acosta, but she ran off with Mamoulian instead.

Mercedes got depressed and suicidal back in L.A.

Garbo got the clap.

And that may be the end of the story of Greta Garbo and me in Death Valley.

Unless Natalie’s signature turns up in Bessie Johnson’s guest book….

The Girls: Sappho Goes to Hollywood by Diana McLellan has been reissued by Booktrope. buy it here on amazon. It’s a great read. And lest you think that time only curves in the California desert, don’t be surprised to learn that I typed this post in a cybercaf����é to strains of “Laura” and “Lili Marlene.” Serendipity? Or destiny?

#MeetMeInAnHour

#MeetMeInAnHour

Pour ou Contre (For or Against)

Pour ou Contre (For or Against)