May 1, 2020

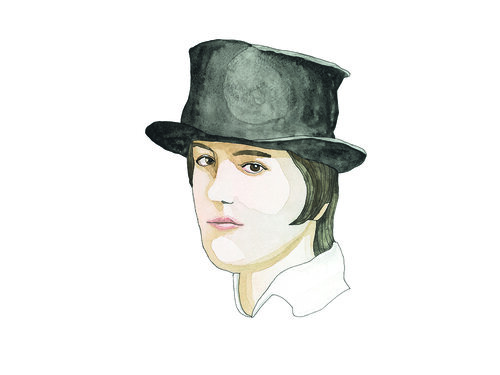

Romaine Brooks by Forsyth Harmon

The Heroic Feminine

and other characters from “A Night at the Amazon’s”

Romaine Brooks Turns 146

Romaine Brooks was a voracious reader. One hundred years ago today in 1920, when she would have been waiting impatiently for Natalie Barney to turn up with birthday cake so they could celibrate, I imagine Romaine Brooks alone at home with a book and a steaming cup of coffee so strong that the spoon stood up on its own. She was contented to spend days at a time like this—as long as it was her choice. When solitude was imposed upon her, not so content.

Sound familiar?

The global influenza pandemic of 1918 had been over less than a year in May of 1920. During the second wave, the lethality was such that one night, four perfectly healthy ladies gathered to play bridge and said their goodybes before midnight. By dawn the next day, three of them were dead. That pandemic came in three waves and infected a quarter of all humans on Earth and killed more people than World War I, soldiers and civilians combined.

Ida nursing the war wounded

While waiting for Romaine’s birthday myself, I leafed through Cassandra Langer’s 2015 biography. I was reminded that Romaine hadn’t just survived the devastation; she had been determined to record it. And fully engage with its horrors. Romaine Brooks, a Philadelphian born in Italy, never considered leaving Europe during the war. She volunteered for ambulance duty on the front lines in France and used her wealth and influence to set up a fund for wounded soldiers. She pushed through as an artist to produce the masterpiece above. It’s a portrait of the woman who was her lover when the war began: Ida Rubenstein, the Lady Gaga of her day. Rubinstein had name recognition and star power. Everyone in Paris knew her on sight. Romaine’s portrait made her a Madonna for the relief effort.

It is hard to envision Ida Rubenstein, patron spirit of the Ballets Russes’ most erotic productions, nursing the war wounded. Before the Great War, her transparent costumes, outrageous movements, and passionate love affairs had scandalized many people in Paris, but now even she readily submerged her flamboyant personality for the sake of the country she loved. Ida responded by turning the Hôtel Carlton in Montmartre into a hospital for wounded Allied troops. Astonishingly, she transformed almost overnight from extravagent fashion plate to competent nurse, caring for the wounded herself.

Art didn’t play second fiddle to politics for people under extreme stress, the way it does today. Art had essential nutrients. Everybody knew that. You couldn’t just stop being an artist, even with the world falling apart. Art and service went hand in hand for Ida and Romaine.

Rubinstein also used her celebrity status to raise money for the war effort by giving public recitals of Montesquiou’s wartime poetry from his Offrandes blessées.

—from Romaine Brooks: A Life by Cassandra Langer

Langer comments that as an artist, Romaine considered it her duty to keep making art under duress, “confronting the enormous taks of depicting her feelings about the war.” Ida Rubenstein, dressed as a nurse towering over the ruins of Ypres in The Cross of France, sums up Romaine’s observation that a hundred years ago, our broken world yearned for the heroic feminine. Today, it still does. Sitting with her coffee in 2020, Romaine might be pleased to read this Forbes article by Stephanie Denning, “Why Have Women Leaders Excelled at Fighting the Coronovirus?”

Natalie: She brightened things up

Eventually, of course, Natalie Barney would turn up to brighten the pensive mood.

Natalie Barney: another rare American who’d stayed in Paris during the war because she couldn’t bear to be parted from her love, Lily de Gramont—a good friend of Romaine’s—who lived up the street. She’d just had a birthday last week.

Lily: She lived up the street

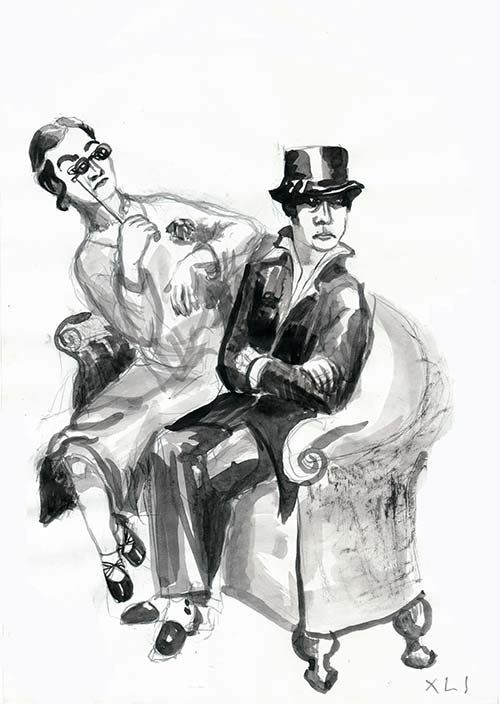

Now Romaine and Natalie were also in love. And somehow it was all working out between the three of them. And would for life. Plus, there was cake.

And somehow it was all working out

You can taste the flavor of this post-pandemic mélange and others in a fun book that’s great to read under a stay at home order, The Art of the Affair by Catherine Lacey, Illustrated by Forsyth Harmon. The portraits you see here are all available for sale from Harmon’s site. Don’t you think they’ll make fabulous birthday presents for the iconoclasts in your life?

Their sort of book

Back on you, Mrs. Brooks, I brought you something completely different for your birthday this time. Different from this afternooon’s impending delights (and the muguet you’ll be expecting later today from Lily). I spoke into a modern sort of gramophone horn and recorded scenes from the cast of characters in your life, all gathered for a birthday party at Miss Barney’s. Pierre Loüys once called her “the young lady of the future society,” which is why you won’t attend this party for six more years. But in 1926, you’ll be walking through this door (listen below) to greet your posse of famous feminines—heroics and eccentrics and free spirits alike. Some of them even men!

Click here to listen to another installment of “a Night at the Amazon’s” Audiobook on soundcloud

In the coming weeks, I’ll be looking for a patron to fund production so people can finally see you on the stage of their imaginations through something magical we’ve got these days, called Audible. I think you’d like it. And I’ll give my artist’s royalty to charity for doing good in the pandemic. Which goes without saying, I can hear you say.

Many happy returns of May Day to you, Mrs. Brooks. 146 looks good on you, even with extreme social distancing. That’s me tipping my hat on the bicycle path in the Bois.